Not that every city should look the same, but sensible disabled-friendly infrastructure helps everyone.

Visual impairment in numbers:

Worldwide, the proportion of total blindness is 0.55%, and about 7% of the population have mild to moderate vision impairment [1]. In India, these proportions are higher: 0.9% and 10.6%, respectively [2]. While it affects people of all age groups, the majority of the people are over 50 [3]. In Indian cities, this proportion is expected to be higher as people flock to cities for employment opportunities, infrastructure, and services such as better healthcare and educational facilities catering to the visually impaired people.

While the proportion of visually impaired people is small, the question arises: why should we plan and design our cities to be more accessible for the small proportion of the population that is blind? In light of the resources and costs that designing inclusive cities incurs, is it reasonable to cater to this population at all?

Why design and plan visual impairment-friendly cities?

Simply put, it is humanitarian, a basic right of everyone, and socially inclusive to all disabilities, including visual impairment. It also has a compounding effect as ‘barrier-free’ design is widely inclusive:

- Providing universal ease of access for all age groups and genders.

- Especially helpful for other disabilities, such as people who use wheelchairs.

- Helpful for the elderly, women, parents with strollers, and children.

- Beneficial for people with temporary illnesses or injuries.

Cost considerations: Although the initial investment may be higher, the long-term economic benefits for all age groups and people with disabilities, along with improved ease of access, far outweigh the costs of not planning and designing for inclusivity.

What is barrier-free design?

Barrier-free design refers to the design of environments, buildings, or products such that they are safe to access and unhindered by obstacles for movement for everyone, regardless of disabilities, age, gender, etc. [4].

In the built environment:

- Indoors (e.g., schools, hospitals, transport stations):

- Adequate space for wheelchair access and walking with white sticks/crutches.

- Tactile markings on the floor.

- Outdoors (e.g., streets):

- Footpaths without bollards or barriers, with predictable flow.

- Ramps at grade differences.

- Traffic signal crossings with sound.

- Signages (preferably symbols) with tactile markings.

- Handrails where necessary.

For mild to moderate vision impairment:

- Hoardings and signages should be placed at certain heights and with specific text sizes to ensure visibility.

These features must be incorporated into policies and planning through:

- Laws.

- Building bylaws.

- Development control regulations.

- Design manuals and guides.

- Building approval stages.

What are the policy provisions for blind-friendly cities?

India has several provisions in place:

- The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPWD Act, 2016): Forms a legal basis for inclusive planning and design [6].

- The National Building Code (NBC): Provides comprehensive guidelines for designing disabled-friendly built spaces [8].

What about the design implementation?

Despite policy provisions, the on-ground situation is disappointing. While spaces like city metro stations follow barrier-free design standards, streets and footpaths remain difficult to navigate even for the able-bodied. Common issues include:

- Cost constraints.

- Negligence.

- Constant repair and maintenance in rapidly growing cities.

Examples of Best Practices and Practices to Avoid

| Sl. No | Best Practices | Practices to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  Image source: Lalit, S. (2018, March 18). Meanings of Tactile Paving: A Blessing for Persons with Visual Impairment. WeCapable. These footpaths with tactile markings: straight dashed lines for safe direction and dotted markings for caution can be felt with white sticks and are accessible to the visually impaired. These roads are also barrier-free. |

Image source: Mirror, B. (2022, February 16). Footpaths: Is decentralised planning the way forward? Bangalore Mirror. The TenderSure roads in Bangalore are not wheelchair friendly; nor are they barrier-free since they have bollards along to dissuade two-wheelers from using the footpaths. On the positive side, they have adequate width and have ramps where there is grade separation. |

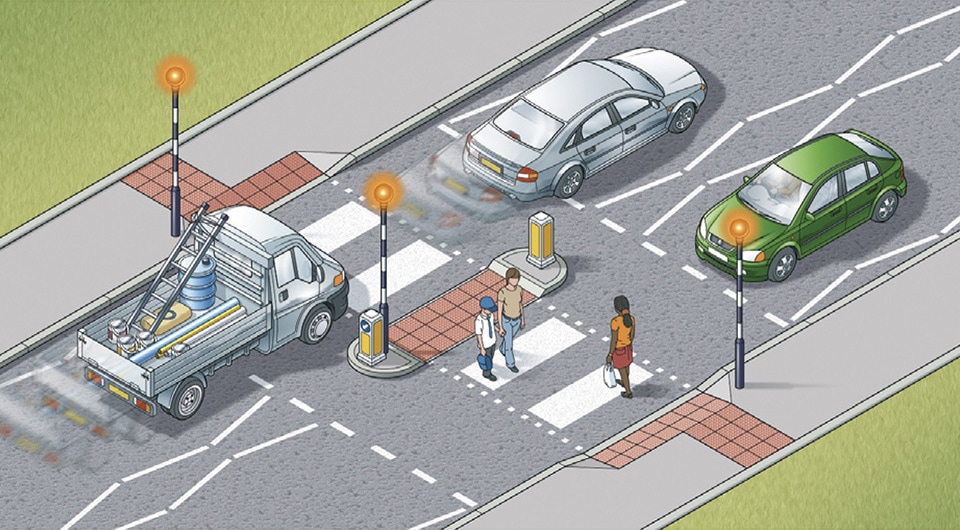

| 2 |  Image source: Rules for pedestrians - Crossings (18 to 30). (n.d.). THE HIGHWAY CODE. Retrieved July 4, 2024. Grade-separated footpaths should have ramps at crossings and accommodating safe islands in the middle and tactile markings are examples of inclusive design. |

Image source: Tiwari, G. (2022, June 15). Walking in Indian Cities – A Daily Agony for Millions. The Hindu Centre. These crossings are un-navigable and dangerous. While this may not necessarily be a pedestrian crossing, several pedestrian crossings often are grade separated by the median and do not have even zebra-crossing signs. |

| 3 |  Image source: Vaidya, A. (2017, August 7). Aundh smart city road: Good public initiatives need good implementation too. Hindustan Times. Barring that two-wheelers are riding on the footpath, this stretch of road in Aundh, Pune, has a good, barrier-free street design. |

Image source: Jhangiani, A. (2024, April 29). Missing footpaths irk pedestrians across city. Times Of India. Discontinued, encroached, ever-changing and under a constant state of repair and maintenance, especially around construction sites are a hazard. |

What else can help provide solutions?

Addressing gaps:

- Map streets and spaces with disability-friendly infrastructure to identify gaps.

- Create tactile maps for visually impaired users.

Awareness:

- Start awareness programs at schools to sensitize children and families.

- Encourage citizens to demand better urban designs.

Stakeholder involvement:

- Engage visually impaired individuals during the planning stages to understand their challenges [9].

References:

- Bourne, R., et al. (2021). Trends in prevalence of blindness and vision impairment. The Lancet Global Health. Link.

- IAPB Vision Atlas (2020). Country Map & Estimates of Vision Loss. Link.

- World Health Organization (2019). Eye care, vision impairment, and blindness. Link.

- UNNATI & Handicap International (2004). Design Manual for a Barrier-Free Built Environment. Link.

- Bansal, K. (2021). Review and Evaluation of Policy Landscape for An Accessible Safe & Inclusive City. National Institute of Urban Affairs. Link.

- RPWD Act, 2016. Link.

- United Nations (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Link.

- National Building Code of India (2017). Part 3 - Development Control Rules. Link.

- Cushley, L. N., et al. (2022). Navigating the Unseen City. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Link.

Bibliography:

- Shahraki, A. A. (2020). Urban planning for physically disabled people’s needs. Spatial Information Research. Link.

- Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment. Link.

- Pineda, V. S. (2020). Building the Inclusive City. Springer International Publishing. Link.

- Wijunamai, V.Q., & Thakur, M. (2023). Making Data Work for Persons with Disabilities. UNESCO Digital Library. Link.

- Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI) Guidelines (2015). Link.